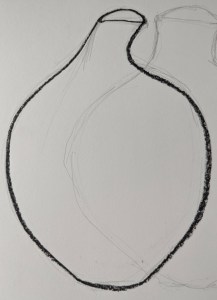

Unbelievably, I didn’t take a decent photo of the third ceramic piece to become a poem in my Tees Women Poets @ MIMA residency, but here are some examples of Deirdre Burnett’s other work to give you a flavour. The one on the right is closest in colour and finish, but imagine it looking much more like an eggshell. The porcelain is also eggshell-thin, and quite small (ostrich egg?)

Egg Fiction draws on my own memories of collecting eggs and family folklore about witches’ boats. I learned charcoal animation for the resulting digital poem, and tried to keep a childlike feeling to the flow of images. I named the poem Egg Fiction because it is in no way an actual biography of Burnett’s route into ceramics.

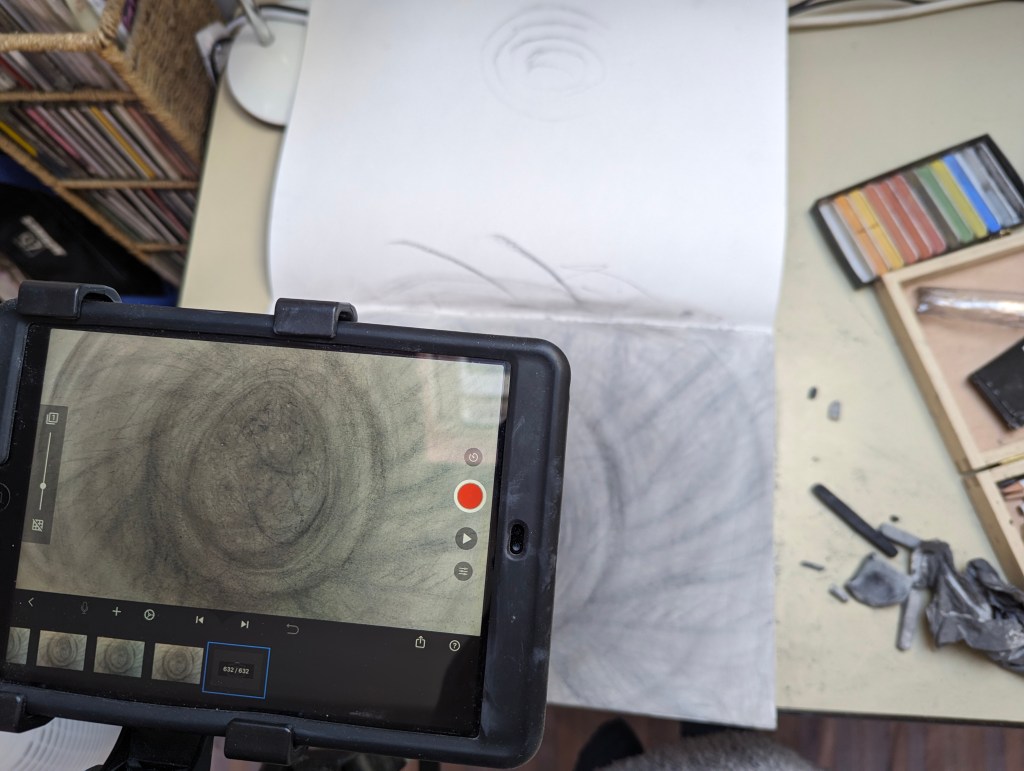

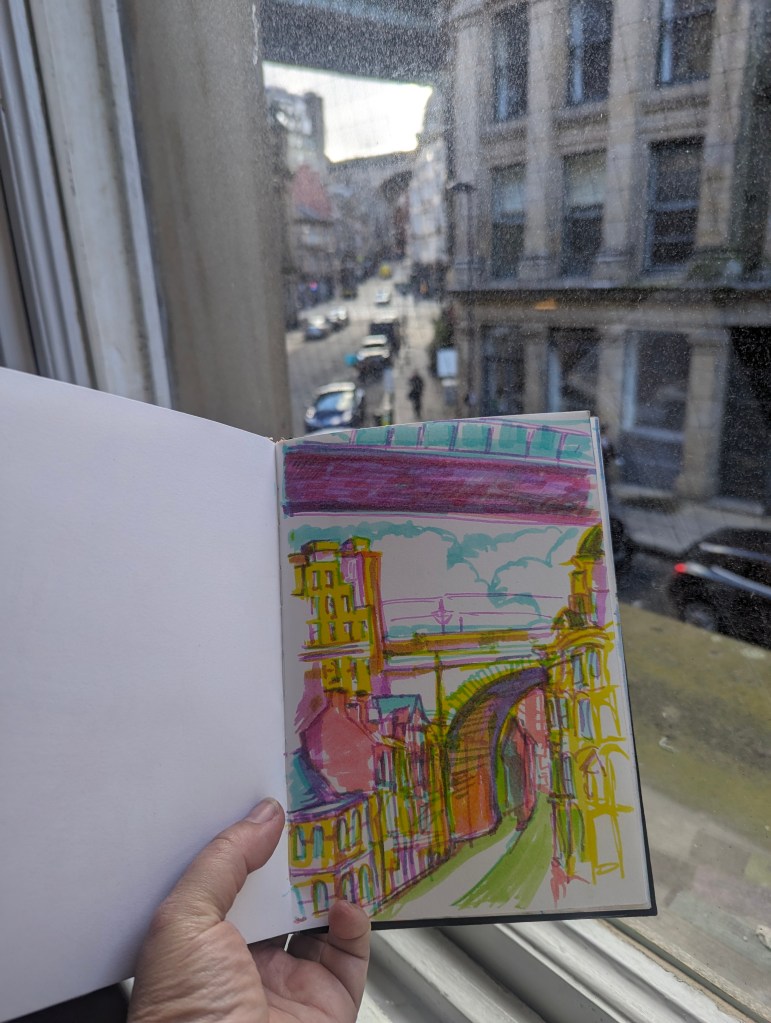

The animation was entirely unplanned and freeform. I used a central egg motif, and simply kept doodling in and around it using charcoal and chalk, taking 2 shots every couple of marks made, using the free app StopMotion on my ancient reconditioned iPad mini. I didn’t do separate drawings frame by frame, every frame was drawn on the same piece of paper. Rubbing in, sweeping off dust, erasing, chalking over, layer upon layer over a combined total of around 8 hours, until my desk was grey and grubby! Completely backbreaking, utterly obsessive…

1500 frames later, having made a whole 58 seconds of film, I recorded the voice track for the poem and was devastated to see it come in at nearly 3 minutes long! Nooooo!!!! Radical editing of words ensued, but I was still only half way with the visuals. Physically unable to continue with hand-drawn animation, I came up with an ingenious solution to triple the length of the film. Importing the original animation into iMovies, I duplicated and layered the sequence over itself, using the editing app’s greenscreen feature to set first the darkest parts and then the lightest parts of each frame as a greenscreen. In this way, the rapidly metamorphing egg began to ghost itself…

Here’s the text for this most challenging and enjoyable piece. When I show you all four finished films in my next blog, you’ll hear that the voiceover for this poem is not me speaking. In fact, I had my first foray into AI-generation by using a text-to-voice app. There were many accents to choose from, and male and female voices of different age profiles. When you read the poem below, what voice can you ‘hear’ in your head? What accent would you have chosen in my place?

Egg Fiction

nanna sent her to steal an egg

fresh from the straw

the darkness clucked

it was the end of the world

it was a rite of passage

don’t trip!

don’t smash it!

don’t smash it too soon

soft-boiled children must learn

the tap the crack the dip the scoop

now smash the empties!

scuttle the coracles

so witches can’t sail to sea

with their wicked, wicked storms

but that warm, smooth weight

had ordained her palm

it’s enough to make her grow up a potter

throwing porcelain

not to shatter, but

to release the paradox-

strength and fragility are twins

this is the earth whose yolk brews wings

this is the earth that knows fire

in the kiln it turns into a little sun

little pitchers become themselves

or smithereen…

look, this bowl has hatched a dragon!

half-shell with a scorched equator

and in the bottom

freckle-speckles

like the memory

of a hen’s egg

The Tees Women Poets are currently open to applications for their autumn residency at MIMA’s Towards New Worlds exhibition. If you’re a woman poet in Teesside, especially if you identify as disabled or neurodiverse, take a look at the info and apply here.